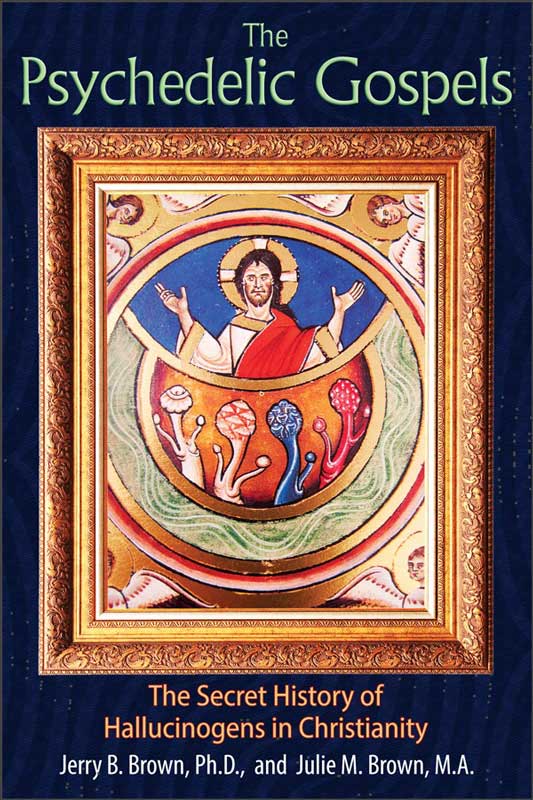

Our theory of the Psychedelic Gospels suggests that psychedelics played an important role in the origins of Christianity; and that the ongoing significance of psychedelics in Christianity is visually documented by their presence in early and medieval Christian art found in churches and cathedrals throughout Europe and the Middle East.

Five psilocybin mushroom caps are painted above the youth greeting Jesus

(Photo credit: Julie M. Brown)

We are not the first to propose a psychedelic theory of Christianity. One school of thought believes that psychedelics were rarely used in Christianity and then only by marginal cults. Based on passages from the Canonical and Gnostic Gospels, and on widespread evidence of psychedelics in the high holy places of Christendom, including Chartres and Canterbury, we conclude that they were present from the time of Christ up through the High Middle Ages.

Another group of scholars concurs with John Marco Allegro’s original thesis, presented in The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross (1970), that visionary plants have always been used in Western culture and religion throughout the ages. We agree. However, these scholars also endorse Allegro’s radical interpretation of the Old and New Testaments, which concludes that the Jesus of the Gospels did not exist, but was rather a metaphor, a code name, for the psychoactive Amanita muscaria mushroom.

We admire Allegro for being one of the first academics to call attention to the fundamental role of psychedelics in religion. Nevertheless, our theory differs from Allegro’s in three ways. First, while Allegro denies the existence of Jesus, we believe that Jesus was an historical figure. Second, while Allegro bases his theory on the speculative interpretation of word fragments in ancient languages, we base our theory on the plausible identification of psychedelic icons in religious art. Third, while Allegro hopes that his writings will liberate people from the thrall of a false Christian orthodoxy, we hope that our discoveries will educate people about the history of psychoactive sacraments in Christianity.

Given the controversial nature of a psychedelic theory of Christianity, we call for the establishment of an Interdisciplinary Committee on the Psychedelic Gospels to evaluate psychedelic images in religious art from around the world.

While our theory focuses exclusively on Christianity, other researchers propose that psychedelics have had a far greater impact on human culture and evolution. In Persephone’s Quest (1986), sacred mushroom seeker R. Gordon Wasson contends that religion itself was first born out of man’s consumption of visionary plants. In The Divine Spark (2015), best-selling author Graham Hancock argues that psychedelics were the catalyst for the birth of civilization some 30,000 to 40,000 years ago. And, in Food of the Gods (1992), psychonaut Terrance McKenna proposes a “stoned-ape theory” of human evolution.

Today’s “Psychedelic Renaissance” will undoubtedly generate renewed interest in the ways in which sacred plants may have stimulated quantum leaps in the human mind.